The Dilemma of Running Conventions in Southeast Asia

As we have went through the maturity of the pony fandom, we’ve seen many pony conventions that has risen and folded through the past eight years of Generation 4’s reign on our lives existence. We’ve seen this niche community go through its grassroots inception, into being one of the greatest phenomenon the internet has seen in regards to fandoms that orient to one single, specific show and franchise. We have broken borders on who can enjoy content, and what kinds of grand social events we can nurture. All around the developed world, conventions sprung up from the North Americas and Mexico to Australia, taking the long way through the UK, the Schengen states, Russia, Japan, China, Taiwan and Southeast Asia.

Albeit in this trek, it’s rather interesting to note that, even with the population that outmatches the Northern Americas or Western Europe, we’ve seen far, far less conventions that breaks the 300 attendee mark in Southeast Asia. This little corner of the world, with budding countries and democracies, provide some of the most challenging terrains possible to run a convention, despite an audience that are mostly financially affluent enough by income to make a quick, three to four day dash, to a neighboring country.

In this blog, I’d like to write about the things that we convention founders and runners in Southeast Asia has continuously faced since the first days we decided to start seriously thinking about hosting conventions, and just what unique and stringent challenges are considered daily in magnitudes and emphasis that differs from conventions in developed countries. I’ll be speaking off my experience of running SEAPonyCon’s installments, or as much as I can without exposing private information.

In general, when running a pony convention, or in fact any niche community convention (such as furry conventions) that don’t integrate well with anime - the most understandably biggest pop culture conglomeration in Asia, even above aggregated comic cons - we’d usually always consider the realistic magnitude of our event first and foremost while making all of our decisions. Again, as we can’t be expecting the attendance metrics of anime and general pop culture conventions, we don’t have the strength of numbers, so we have to always, always consider the cultural context that we’re in.

Since I will be talking from the perspective of an international event that Project SEAPonyCon was, and what Fiesta SEAPonyCon is, I’ll be putting greater emphasis of how we consider the more stable economies of Southeast Asia - Singapore, Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, and perhaps the more affluent populations of Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, Cambodia, and East Timor

The tl;dr is, we all generally have to consider

- Our income

- The volatile economy of each country

- The exchange rate and the US Dollar

- World politics (yes, not just Southeast Asia)

- Actually getting attendees to attend

- Getting panelists, musicians and vendors to attend

- Convincing people to spend on something intangible and unproven, such as a first time convention with no track record

- Convincing parental consent, or providing means to accomodate parents, including parents of adult attendees

- Pricing of tickets, by averaging on the least powerful currency of the nation

- Language barriers on announcements, interactions, and even the convention itself

- Penetrating as many social media platforms as the region uses

- The infrastructure, reachability, and convenience of hosting a convention vs cost of hosting in that country/city

- Flying

- Immigration and customs, as most logistical needs will most likely fly internationally one time or another

- Different laws and policies pertaining to events, on any host country

- Angel donators

- Being in debt for the foreseaable future

And of course, this all goes on top of the general convention debacles of planning the event, finding a venue, logistics and operations, financial bookeeping, program planning, commissioning of artwork and power assets, paying for voice actors and special guests, internal and external drama… you name it.

The Southeast Asian Economy

CouchCrusader on Twitter corrected me recently that he was asking about what people would do with 50 thousand US dollars, not batshit insane amounts of money.

Well let’s see how much that money stacks up. Let’s take Indonesia for example - unfortunately my home country, the largest country of the region, and the source and scapegoat for Singapore and Malaysia’s air quality problems.

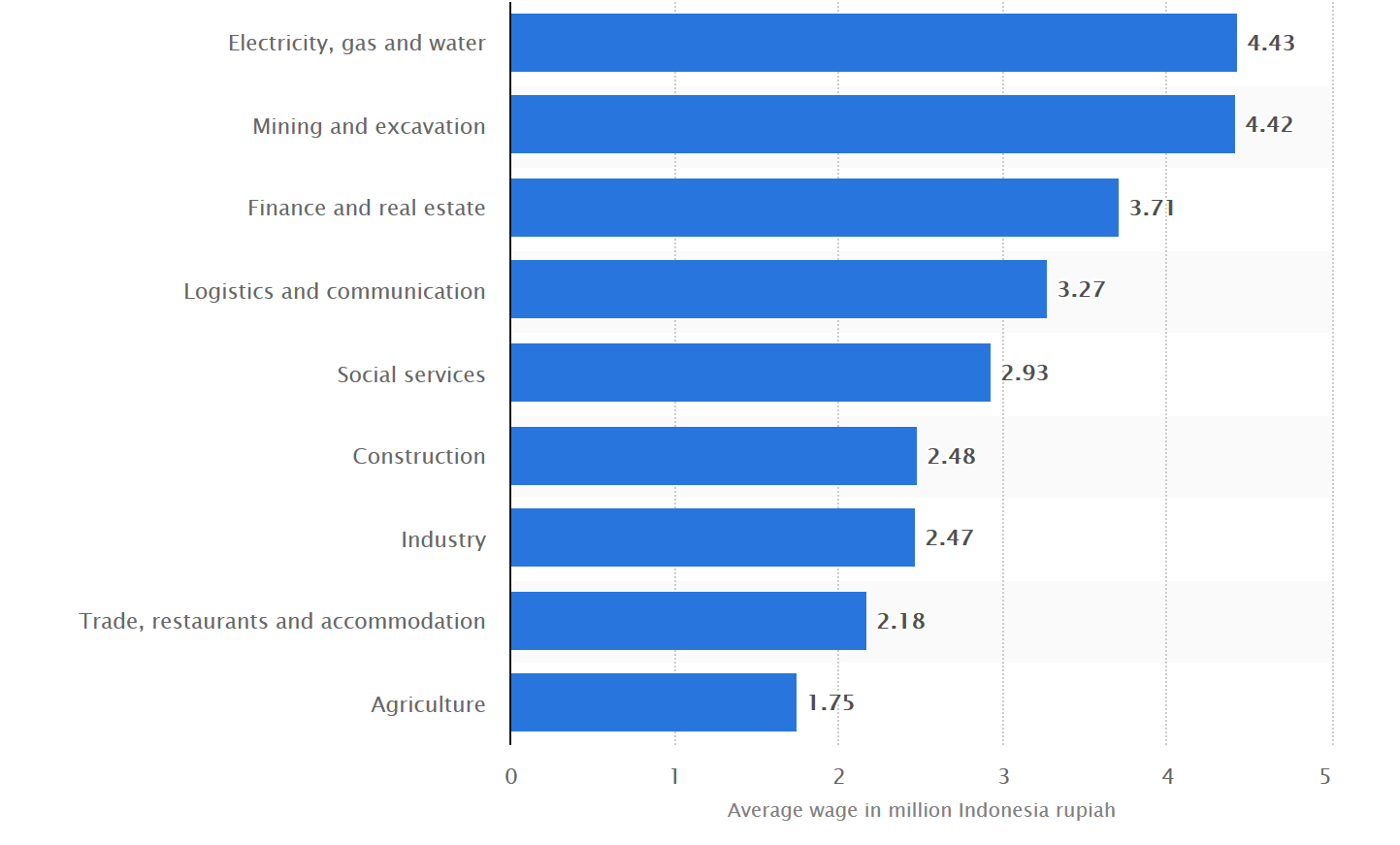

(Data by Statista)

(Data by Statista)

Now let’s just take the upper quartile of that and assume the average wage of the country is 4 million Indonesian Rupiahs per month. With the USD to IDR exchange rate as of 27 September 2018…

…that’s not a lot of money. In the international scale. And that’s before taxes. Taken when the IDR is at its lowest points in history to the US dollar, in response to the US Federal Reserve increasing interest rates and its trade war to China, Turkey and Iran (we’ll talk about politics later).

But that’s just part of the story. Currently, we’re only seeing just how much anything that’s priced by the US dollar would cost in Indonesian rupiahs. Sure, that tells something about how weak the Rupiah is to the dollar, but to gain a deeper understanding of just how much every Rupiah means in terms of dollars, we use another tool called the Purchasing Power Parity. This is an economic metric that is used where a theoretical “basket” of common things that you’d generally find in any country, would cost if you’d buy the exact same things in another country. This helps describe just how much every unit of money means to a household. Another tool that can do this is the Big Mac Index - that uses the price of Big Macs as the “basket” to measure Purchasing Power Parity.

I usually use this site that pushes PPP indices regularly from the World Bank.

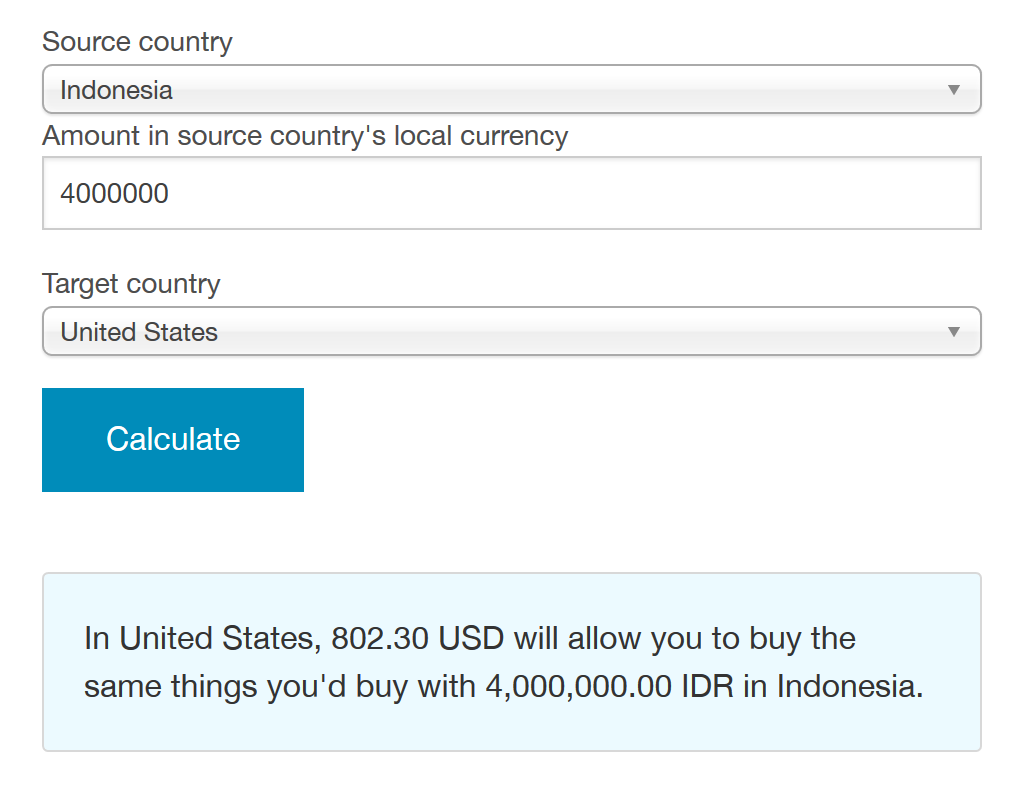

So let’s see how much that 4 million Rupiahs would mean to an American…

And on 27 September 2018, 802.30 USD is almost 12 million rupiahs, almost three times the salary of the average Indonesian.

So what’s the point in me outlining all of this? Well, firstly, I’m not a certified economist and my bachelor’s degree is in Computer Science. But, it’s an honest attempt from me that provides you with one example with how much money is actually worth for people across borders and across boundaries. The average Indonesian, who earn and live with IDR on a daily basis, not only has to go through the hardships of the high exchange rate of the US Dollar, but also perceive anything that is priced to US consumer standards as at least three times more than what price they’d perceive it to be, based on local prices of similar goods.

In contrast, a Singaporean doesn’t see this much of a difference. On average, Singaporeans make 5119 SGD a month (that is, they make almost 14 times an Indonesian does in a month). When compared with the Purchasing Power Parity index, that money can afford the same things 4340 USD can do in the US. And when that’s converted back to SGD, it’s about 5955 SGD - just 16% above their average wage, instead of 300% like the Indonesians perceive.

You may wish to repeat this exercise with the average wages and purchasing power parities of Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand, and all the others. We have to account for all of those too if we want ot invite them.

Another way of seeing this without performing much calculation is by examining their GDP Per Capita, which provides a rather good illustration of just how much money the average household makes in their countries in US dollars, which provides a rather pertinent baselines on what you’d expect average goods and services to sustain life and civilization would cost in the different countries.

The different countries around Southeast Asia all have their different purchasing power parities, average wages, and costs to attain their own standards of living, putting currency and economics into play with something as basic as running a small pony convention. These are things that most states from the European Economic Area doesn’t really have to worry about, as most of them trade in Euros (despite having different purchasing power on different countries - albeit not by much), and definitely not something large, domestic populations of bronies in the US, China and Japan have to think about either.

But of course, with higher wages, you’d also need to take account on the higher standards of living and taxes, which is usually indexed by the Purchasing Power Parity. You’d also have to account for other macroeconomic factors, such as inflation adjusted income per person, Gini coefficients and the Human Development Index, that usually comes vis-a-vis with how much spending money an average citizen of each country can save. All of this contributes to the equation of measuring the baseline feasibility of simply getting people to be attracted enough to save up.

It’s also important to note that, with fluctuating oil prices and the Iran and Venezuela crisis, we have to account our reliance on flying to conventions with an increasingly US dollar based aviation industry. Ticket prices are rising dramatically compared to the purchasing power of most Southeast Asian nations, and the act of thinking of flying to a convention is no small matter with the average wages of these countries.